TLDR; Through the development of selective sample concentration for Tuberculosis Diagnostics, a key learning for us from the technology standpoint was the performance difference in being able to handle small and large samples. Most In-vitro Diagnostics (IVDs) are designed for small samples. Think about it. A PCR is $20 per test. But it is also $20 per 20ml? What happens when you have 20,000ml of sample? There’s almost always ongoing outbreaks and recalls in the food safety space. Our diagnostic tools are built for the wrong scale, and it is costing us billions.

/

—

Infectious Disease Transmission: $8 problem turns into $8000

Imagine you’re travelling with a group. You run out of water and decide to borrow water from someone in your group. After the trip, most everyone falls sick. What happened?

It is possible, that like you, this person also ran out of water, and decided to say fill water from a clear looking stream nearby. Which may’ve had bacteria. Which then everyone drank from.

This is a very typical scenario for disease transmission.

But how are we tackling it? Well, the original water bottle was problem tested at the time of packaging. The next time anything gets tested though, is going to be at the doctor’s. Average Salmonella illness ER visits cost about $500. For a 10 person group, the total medical cost becomes $5000. If everyone also loses a day of work recovering, for median income, that’s another $3000 for the group. So a total loss of $8000. The funny bit is, a water test to prevent this will cost you $8 on Amazon. Do you see what happened here? An $8 expense blew up 1000-fold.

/

Minimum information required for decision-making

Now, there’re a lot of good tests to test people when they present with sickness. There’s a whole bunch of companies that’re making cleverer PCR based tests, for example. However, as the example shows, it is much more cost effective to ‘prevent’ sickness in the first place. Because while PCR tests at the doctor’s give us a lot of very useful information, they’re not cheap. And may therefore be the incorrect test to use here, because the actual meta-question that needs to get answered before we test the water is, What is the minimum amount of information required to make a decision? What fidelity levels of information do we need?

/

Volumes: A subtle but important product spec

As we shift from the realm of diagnosis to say, surveillance to prevent sickness, an important subtle shift occurs. When we test humans for sickness, we work with the amount of fluids humans can give us. When we work with media that we come in contact with (such as air, water, food), we need to work with volumes that’re 1000 times higher. Human samples are about 5ml. Food samples are 50,000ml. As you expect, diagnostics (esp IVD) designed for humans have limited effectiveness here.

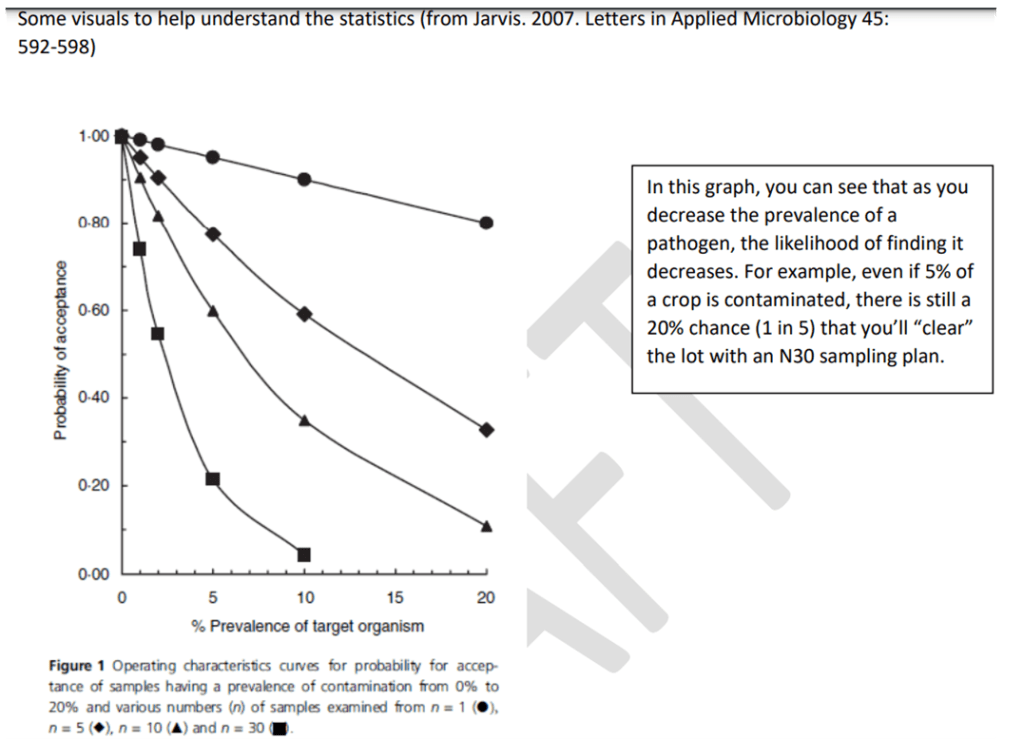

How is, say PCR, used for testing food lots? Well essentially, you use statistical methods. You ‘sample’ the large lot in a way that your total sample, representing the lot, fits into the PCR. A modest 100 liter lot-runoff needs to fit in 5 ml.

It is easy to see the limit of this approach. Lettuce for example, is a commonly recalled item. What happens is that after harvesting, lettuce is washed and processed. It is easy to see that machines and water used during this processing can get contaminated, contaminating other lots. As the global population, and feeding requirements increase, the inadequacy of the current solution is only going to exacerbate.

/

Similarity to Cybersecurity

In terms of scale, the whole thing is pretty similar to cybersecurity in a way. There’s software to protect each computer, but when you have an entire private network, protecting the network from attacks in the first place, makes more sense. That problem is different than one for protecting each computer though.

Here’s a table from world famous expert, Claude.ai, showing the similarities in both problem mazes.

Systems Perspective: Network Firewalls vs Food Safety ‘Firewalls’

| Aspect | Network Firewalls | Food Safety ‘Firewalls’ |

|---|---|---|

| Volume of Processing | High: Millions of packets per second | High: Large volumes of air/water constantly processed |

| Processing Speed | Extremely fast: Microsecond decision-making | Fast: Real-time monitoring, quick valve/filter actions |

| Accuracy vs Speed | Favors speed; uses heuristics and rules | Balances speed and accuracy; some tests are rapid but less precise |

| Continuous Operation | 24/7 operation with minimal downtime | 24/7 operation during production cycles |

| False Positives | Common; managed through tuning and whitelists | Less common; managed through threshold adjustments |

| Monitoring Complexity | Complex: Multiple protocols and attack vectors | Complex: Various contaminants and environmental factors |

| Threat Landscape | Rapidly evolving: New cyber threats emerge daily | Relatively stable: Known pathogens, occasional new threats |

| Regulatory Compliance | Strict: Cybersecurity standards (e.g., ISO 27001) | Very strict: Food safety regulations (e.g., HACCP, FSMA) |

| Failure Consequences | Data breaches, financial losses | Health risks, product recalls, brand damage |

And it actually is pretty similar in terms of downstream effects too. In the food industry, depending on how big a brand is (even for less processed items such as produce), average cost of recall can easily fall in the $10,000 – $10,000,000 per instance range. This is a huge market risk but also national and international biosecurity and food security risk. For reference, businesses spend on average from $1,000 – $3,000,000 on cybersecurity annually. This also makes it venture scalable.

/

Different system requirements

But going back to the table, it is important to note that with larger volume processing in a surveillance situation, a system as several basic design requirements that are not compatible with current PCR type systems:

- Very low cost per test

- Almost real-time results

- Almost no consumables for scalability and automation in a real-time setting

Jacob Swett makes the case here about how airborne infection control has not changed in decades, despite recognition of the problem. Indoor air is a leading cause of respiratory illnesses and spreading infectious diseases. Even in pre-COVID era, US spending on respiratory infections $40 Billion a year. And while we may have some systems such as UV-C and even HVAC based ones to affect indoor air, timely assessment of infection in the media we come in contact with, is still impossible with current solutions. And yet when think of testing air, we’re looking at an entirely different set of sample complexity

- How can we even input or handle thousands if not millions of liters of air?

- How do we concentrate, what is effectively, an extremely low concentration sample?

We need a fundamentally different paradigm of testing, to switch to a prevention based model of diagnostics. This also requires a fundamental rethink of the solutions, if not technology.

/

Transmission is the enemy when it comes to infectious disease. We’ve gotten away with it, but COVID-19 has shown that we need to build for large volumes, not just small ones. For the sake of our people and for the sake of our personal and global finances.

At Drizzle Health, we’re calling these Large Scale Diagnostics (LSDs). And interestingly, they have a lot in common with building diagnostics for global health. More on that later!

—

Selective concentration and testing of large samples, for example, is a cross industry problem. This is important because it ultimately limits the intervention of diagnostics to treatment, missing out on the opportunity to prevent outbreaks.

Leave a comment