Originally published on the Drizzle Health Substack

*written with inputs from Iniya and Bonolo.

Perfect Test ≠ Perfect Solution

The discovery of DNA polymerases is said to be the equivalent of discovering fire in the world of diagnostics. When Kary Mullis invented PCR in 1985, it wasn’t just another laboratory technique – it was a revolution. Scientists could take tiny fragments of DNA and create millions of copies in just hours. A single hair strand or drop of blood suddenly contained a universe of information. PCR rightfully took home the Nobel Prize, and we’ve been building our diagnostic world around it ever since.

PCR became the darling of global health philanthropy. Major donors like the Gates Foundation poured hundreds of millions into rolling out PCR-based diagnostics across the developing world (and development, as in case of GeneXpert). It’s easy to see why: PCR offered unprecedented automation, accuracy and the ability to detect multiple diseases with a single platform. Who wouldn’t want to bring such powerful technology to resource-limited settings?

However, somewhere along the way, PCR shifted from being one tool in our diagnostic toolbox to being treated as the only tool worth having. Like a shiny new hammer that makes everything look like a nail, PCR became the default answer to nearly every diagnostic challenge in global health. Need to test for TB? PCR. Want to track emerging diseases? PCR. Looking to monitor drug resistance? PCR again.

This one-size-fits-all approach had an unintended consequence: it began reshaping healthcare systems around PCR’s requirements rather than around the needs of the communities they serve. Health programs started prioritizing the purchase of expensive PCR machines over strengthening basic diagnostic infrastructure. International funding became tied to adopting PCR platforms, even in places where simpler solutions might have served people better. And while it was expected demand would lend itself to some economy of scale, competition didn’t help cross the technology cost barrier imposed by reagent bill of materials and crowded markets – philanthropic distortion of markets became a necessity for continued PCR rollout and strengthening.

So, is PCR the panacea we thought it would be? Well, it would be a dream come true if it was.

The Reality Check

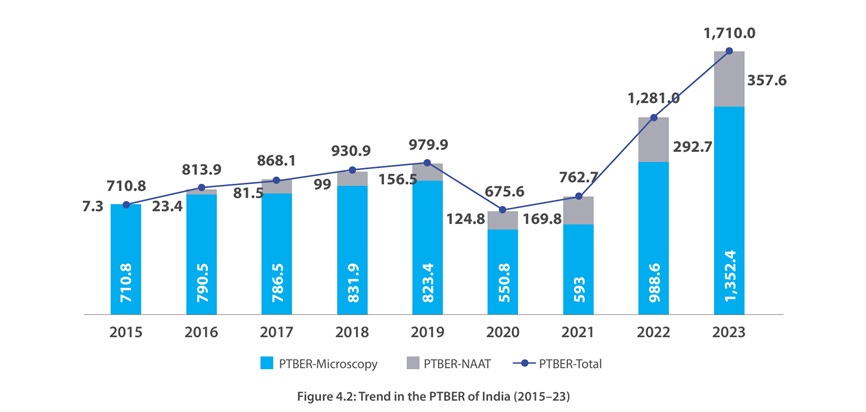

Let’s look at TB testing. In 2023, less than 40% of people diagnosed with TB got a PCR test as their first diagnostic. The rest? They relied on microscopy – a technique that misses about half of all cases. This isn’t because people don’t want to use PCR. It’s because of what it needs to function – stable electricity, temperature control, expensive equipment, trained technicians, and most importantly, money for recurring costs of cartridges.

Let’s look at how countries could be playing to their strengths rather than abandoning existing infrastructure for glitzier technology. Take India, which has built up an impressive network of over 30,000 microscopy centers over decades. These centers form the backbone of TB testing in the country, performing over 70% of all TB diagnoses. That’s not a weakness – it’s an incredible asset. We’re talking about a system that reaches into nearly every corner of the country, operated by skilled technicians who know their communities.

Nigeria faces similar challenges but with even more severe resource constraints. Their GeneXpert machines operate at only 27 % capacity because they can’t afford enough test cartridges at US$25 – 50 each. It’s like having a fantastic car but no money for gas. These aren’t isolated examples – they represent the reality in most high-burden TB countries.

The Hidden Opportunity

But here’s where it gets interesting. While we’ve been focused on getting PCR everywhere, we’ve undervalued the possibilities of tools that exist. Instead of trying to replace this entire network with expensive PCR machines, what if we enhanced it? Take microscopy – yes, the same technique that misses half of TB cases. Countries like India have already invested in training, infrastructure, and community trust around these microscopy centers over decades. They have last mile access that hub-spoke models have a hard time matching. When we looked at microscopy, we realized that there were no physics limitation causing its abysmal performance. Rather, how samples are prepared. Our $1 MagnaSlide product, therefore, works with existing microscopy infrastructure and boosts microscopy accuracy from 50% to 95% for just an extra dollar per test.

Think about what this means for countries like India. Those 30,000 microscopy centers represent decades of investment in infrastructure, training, and community trust. Instead of trying to put a $17,000 PCR machine in every clinic (plus $10/test after subsidy), we could dramatically improve the diagnostic tool that’s already embedded in communities for the price of less than a cup of coffee. This isn’t about settling for less – it’s about being smart with what we have and building on existing strengths.

A Better Way Forward

Don’t get us wrong – we are not suggesting abandoning PCR – it remains an incredible tool for a wide variety of use cases, including in TB diagnosis. But we need to be more creative in our thinking. Here’s what that might look like:

- Minimum information needed for clinical decision-making: Invest in innovations like MagnaSlide that can transform existing tools without requiring a complete system overhaul, keeping the systems sustainable and insulated from aid shocks. A focus on minimum information required also prevents further transmission in the community – ‘stop the spread’ is as important as diagnosis for TB, and other infectious disease.

- Think about the whole system: Consider all the costs – not just the price per test, but what it takes to keep the system running day after day.

- Meet people where they are: TB patients often don’t even go to their nearest clinics due to the stigma attached to the disease. Hub-spoke models, apart from backlogs and clogging, need to be designed with such insights.

- Have a plan for over-testing, not just testing: With the large emergence of sub-clinical TB for example (no symptoms to catch active patients), we need to have ways of testing populations in an area repeatedly over long periods of time, rather than sporadically.

In Sum

As foreign aid for diseases like TB is expected to face huge cuts, we need to get smarter about how we detect and diagnose TB. The solution isn’t always about having the most sophisticated technology – it’s about having technology that works in the real world, where people actually need it. At price points that governments can support economically and sustainably. Just like microscopy for TB.

We need to stop molding our healthcare systems around the weaknesses of PCR (more on this in an upcoming post) and start developing solutions that fit the realities of high-burden settings. The best diagnostic test isn’t the one with the highest sensitivity in the lab.

Leave a comment